“Let your life speak” is a Quaker adage. It sounds abstract until you meet someone like my brother-in-law, Don Campbell. Don believed that God finds ways to speak to us and through us. When one looks back at a life– we see the evolution of unique gift and purpose. We see early tracks in the snow, footprints in the sand, bread crumbs on the forest floor… all clues to a life.

Don loved puzzles: jigsaw puzzles, paper and pencil puzzles, mysteries, and math problems. He looked for clues, for patterns, and sorted by shape and color. He sought out the edges to anchor pieces that would fall into place- allowing a clear picture to emerge- where every piece had a place and fit just right. He grew to expect that with attention, things would turn out right. Don loved math. He balanced out equations and tracked the rules of the universe as they sifted in the patterns of daily life. Things balance out.

Like many other boys, he went through Cub Scouts. He had acorn fights with his twin brother, Ben (whom he always referred to simply as “Brother”). They were fraternal twins, but I joked that they were paternal, always telling each other what to do. Throughout all of this, Don showed up every week at St. Mary’s and memorized a new hymn every month, leaning into the beauty of the earth with a deep reverence for all creatures, great and small. Don was fearfully and wonderfully made, as each of us is, and as these early experiences evolved, they enabled and empowered his life to speak.

Looking back, it was not hard to trace the innate pursuits and pastimes of childhood to the threshold of Don’s adult occupation and purpose. Don became an accountant. The pieces had to fit. The scales had to balance. He was good at this. He had a long and successful career with the US General Accounting Office. Among his things is a plaque commending his review of a project in which he saved the government 88 million dollars. He never mentioned this to us–it was buried in a drawer of miscellaneous items.

He served as treasurer here at St. Peters and then as Senior Warden. He was given a prayer book at the end of each of those terms. They were obviously treasured. He kept one on his bedside table (with his own personal prayer list that held many of your names at one time or another) and the other on his coffee table.

There are lifelong bachelors, and there are family men; Don was both. He stayed centered on family life with strong ties to siblings, inlaws, cousins, nephews, and nieces. When he woke up in the morning, his eyes would fall upon the family pictures on the dresser across from his bed. And with those pictures was a stack of maps and guidebooks of places he visited family: New York. Florida. Tennessee. North Carolina. Arizona.

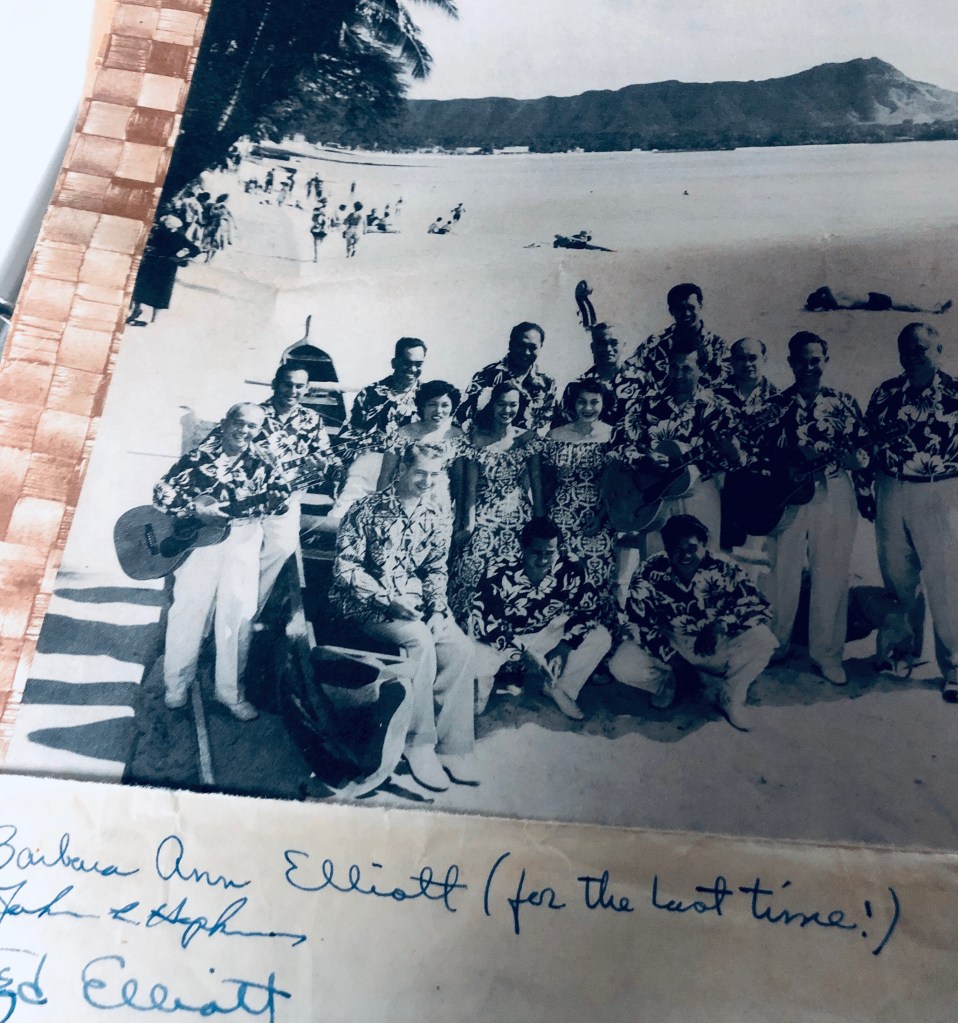

His parents, Ed and Elizabeth Campbell came to a stage in their lives where they were increasingly being honored for their very significant contributions throughout the twentieth century. Don became the point man and advance man for all of that.

Every Sunday, he met his parents here at St. Peter’s and had Sunday Dinner with them afterward. Later, When Elizabeth was widowed, he tirelessly worked to honor her wishes and preserve her dignity and way of life by arranging support for her in her own home; he continued to bring her to St. Peter’s every Sunday and had lunch afterward until she died at 101.

Later, when Don retired, there was a shift, a confluence of events that was transforming. It was his turn. He continued to work tirelessly to preserve family history. But there was more for him to do: he got a personal trainer, Chauncey Grahm; he began to pay attention to nutrition; he formed a foundation as a way of making a difference and hired an interior designer to help him prepare to move into Goodwin House.

Don was increasingly engaged in life-giving action for the rest of his life. He still loved puzzles, but the puzzle pieces were more subtle: What is mine to give? What is mine to do? What am I learning? What do I want my life to say?

He read a book called Godwinks and believed that if we really paid attention, God found many ways to guide us. He insisted that I read it. I didn’t.

“Annie…..”

“I’ll do it,” I said. I didn’t.

“Just read the first chapter,” he implored.

“Okay, Okay.” I didn’t.

The morning he died, I downloaded the book on my Kindle and began to read. I immediately saw the profound influence this book had on his life.

Don was openheartedly generous and earnestly frugal. I found a note that he wrote to Elizabeth Branner, then head of development for Washinton and Lee Law School. He approached her through an email (presumably to save a stamp), “I would like to talk to you about making a gift from my foundation,” he wrote, “Do you have a toll-free number?”

Don was physically frail, with a spiritual and moral fortitude that did not waiver. That physical frailty accounted for an easy irritation. He wore his nervous system close to the skin. His irritation was reflexive, but his kindness, generosity, and love were intentional and comprehensive.

His moral and spiritual fortitude did not waver. He worked hard to be faithful and to be true and strong to the last. Transcending his broken body, he let us know he loved us. He prayed with us. And he let us know he was okay. His heart may have stopped, but it never gave out.

Let your life speak. What was Don trying to say? He kept a stack of index cards with inspirational quotes and prayers. He wrote out the baptismal covenant on one:

Will you seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving your neighbor as yourself?

I will with God’s help.

Will you strive for justice and peace Among all people, and respect the dignity of every human being?

I will with God’s Help.

And he did.

Let your life speak. Don narrowed down what he wanted to say- he narrowed it down to the 3 Ps: Pause. Be Patient. Be Positive.

Last week, I finished a year and a half of chemo infusions, radiation, and more chemotherapy. Then Monday, after working in Don’s apartment all day long. We came home to Richmond. The most beautiful flowers were waiting on the porch. It was a shock, momentarily, to find that they were from Don. He’d arranged for this a few weeks before. He had dictated the card to the florist, ensuring that she got every word just right:

Ring! Ring!

Congratulations on your last treatment after all your perseverance and dedication.

And there it is. There were the two words he spoke with his life: Perseverance and dedication. Let your life speak.

Ring. Ring.

Ring the bell, Don.